The approach to Paro was every bit as white knuckled the second time around as the first. It’s rumored that there are only fourteen pilots in the world qualified to navigate the rapid descent amongst the Himalayan peaks and follow the precise glide path through the valley to land at Paro airport. Looking out the plane’s window, it appeared that at times our wings were about to gently brush the trees on the surrounding hillsides.

While enroute from the airport, we stopped to visit the Rinpung Dzong. We’d visited several dzongs throughout the country on our first visit but Rinpung was one of the larger and more beautiful so well worth a revisit. Dzongs are an integral part of Bhutanese life, once upon a time serving both defensive and religious purposes. The word dzong means both ‘castle’ and ‘monastry’, a similar concept to the fortified churches we’d seen in Romania. For this reason, they were built on cliffs or ridges with commanding views of the valleys below.

Ringpung’s formal name is Richen Pung Dzong, which means ‘Fortress on a Heap of Jewels’. Built in 1644 on the foundation of a former monastery, the dzong was used on numerous occassions to defend the Paro valley from Tibetan invasions. One can still see the remains of catapults used for throwing massive stones on the enemy below.

Today the dzong is used for muncipal government administration and as a monastic training center. Monks in training, many as young as five years, heads shaved and robed in red, scurry through the courtyards. These young boys come mostly from poor families who consider it an honor for their sons to learn to read and write English and Sanskrit and study under the guidance of religious mentors. Monks are well respected in the culture and a big contributor to Bhutan’s renowed chart topping happiness index.

From the a balcony in the dzong’s gathering hall, we had a clear view of Paro Valley. The tentacles of urban sprawl have continued to move down the valley as more and more Bhutanese relocate from rural areas to cities.

We arrived at the Zhiwa Ling hotel in early afternoon. Turning into the winding stone paved driveway lined with flapping prayer flags, we approached the main building with its trapezoidal roof, stone face and multiple rows of painted latticed windows. We were greeted at the main entrance of the hotel by a troupe of dancers, in bright yellow, red and blue attire, chanting, waving flags, clicking a clappers and ringing bells.

The male dancers jumped lifting their knees and bare feet high in the air, spinning and pirouetting to the rhythm of the instruments. Although not masked, the costumes and moves were similar to the cham dance performed regularly by monks at religious festivals. We watched the performers and then went inside to register.

Guest rooms were in three storied units behind the main building; we eagerly retrieved our key and followed the stone path past a small stream and gurgling fountain, climbing the outside steps to our third floor room. The key should have ,been our first clue that something had changed. Instead of the large metal key with tassel we’d had last time (memorable because it was too heavy to carry around necessitating leaving it with reception whenever we went out), the hotel attendant handed us a plastic key card. Opening the heavy, decorative wood door, I gasped! Gone were the traditional furniture, tapestries and antiques that had given the room its character and made it special, replaced by generic bland international hotel décor. We could be in any Hilton or Marriott anywehere in the world! How disappointing – COVID had provided the hotel an excuse to modernize. Snarkily, I hoped National Geographic would rescind its World Heritage designation.

We picnicked on the hotel grounds, watching more dancers and trying our hand at archery. After lunch, we visited a local farmhouse on the outskirts of town. Three generations of the family lived in the home and farmed the neighboring fields growing corn, a variety of root vegetables and raising livestock. A second generation daughter managed the household and she graciously allowed us to tour the house – the family room, bedrooms, shrine room, then settled us at the long wooden table in the kitchen for a corn snack and butter tea. I love the idea of butter tea and wanted to like it – it is often mentioned by Himalayan trekkers as refreshment taken at inns on the trail, but it took a lot of fortitude to drain the small cup. Saltier than ocean water, it has a rancid taste.

Bidding our hostess goodbye, we caught a shuttle to downtown Paro, more to explore than to shop. Bhutan is by no means a shopper’s paradise and its selection of souvenirs is limited. Probably the most unique handicrafts are wooden painted penises; representing good wishes and fertility, these phalluses come in all colors, sizes and styles and are less of a sexual symbol and more of a good luck charm.

A large prayer wheel graces Paro’s center square, covered by a beautifully carved wooden canopy. Like a magnet, prayer wheels attract passersbys and we watched an elderly woman, bundled against the cold, slowly spinning while circling the engraved drum.

We wandered the back streets of Paro to get a better idea of how urban dwellers lived. There was a lot of new construction underway and we watched workers crawl along makeshift scaffolding. The government has a strict set of building codes and standards to ensure that all new construction upholds the philosophy of Bhutanese architecture – design that blends nature, uses locally sourced natural materials and contains no nails or iron bars.

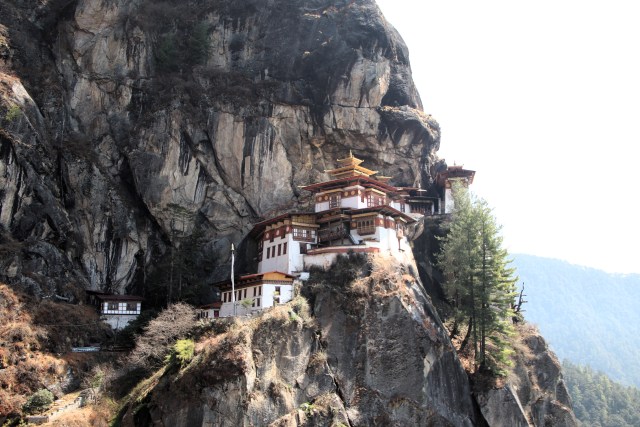

Later that evening, we dined at the hotel restaurant, then returned to our room to be lulled to sleep our bland surroundings.. The next morning dawned clear and sunny, perfect conditions to hike to Tiger’s Nest. My recollection of the hike four years ago was that it was moderately difficult; true, the climb down the eight hundred steps into the valley and then back us as many to the monastery at 10000 fit was a bit heart pounding but overall the hike was manageable. This time the hike seemed much more difficult; not having time to acclimitize to altitude makes a big difference for us lowlanders. Nonetheless it was a beautiful day and the trail was only lightly traveled. Later we realized it was a religious holiday and normally the trail was closed to foreign visitors but our outfitter was able to get us an exception. There were times on the trail where we were by ourselves, reveling in the natural beauty and solitude.

We passed the occasional monk making the pilgrimage to the monastery to pray. Some locals were transporting supplies to the monastery. We watched a young man with a bookcase harnessed to his back manuever down the steep staircase to the valley below and then up to the monastery.

When we reached the Tiger’s Nest, we checked our shoes and backpacks and took a short tour, avoiding the temples where people were praying. We didn’t mind the restricted visit – last time we were here, we spent considerable time exploring the various shrines and temples and besides walking on the cold concrete in stocking feet was bone chilling!

We stopped for lunch at the tea house at the half way point on the way down. This was another COVID improvement – the small shack with its open air patio had been transformed into a spacious restaurant with a large deck. We fortified ourselves for the hike down on Bhutanese staples – rice, chicken and vegetables, enjoying the sunshine and the view as we ate.

Unfortunately, my husband began to feel queasy on the way down. By the time we reached the hotel he was in the throes of the dreaded traveler’s stomach issues, so we spent a quiet evening resting. Tomorrow we leave for the final country on our itinerary, the Sultanate of Oman.